East Tennessee on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

East Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee defined in state law. Geographically and socioculturally distinct, it comprises approximately the eastern third of the U.S. state of

The Blue Ridge section comprises the western section of the Blue Ridge Province, the crests of which forms most of the Tennessee-North Carolina border. At an average elevation of above sea level, this physiographic province contains the highest elevations in the state. The Blue Ridge region is subdivided into several subranges— the Iron Mountains,

The Blue Ridge section comprises the western section of the Blue Ridge Province, the crests of which forms most of the Tennessee-North Carolina border. At an average elevation of above sea level, this physiographic province contains the highest elevations in the state. The Blue Ridge region is subdivided into several subranges— the Iron Mountains,

Chattanooga

''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009. In June 1861, the Unionist East Tennessee Convention met in Greeneville, where it drafted a petition to the Tennessee General Assembly demanding that East Tennessee be allowed to form a separate Union-aligned state split off from the rest of Tennessee, similar to

In June 1861, the Unionist East Tennessee Convention met in Greeneville, where it drafted a petition to the Tennessee General Assembly demanding that East Tennessee be allowed to form a separate Union-aligned state split off from the rest of Tennessee, similar to

TEPCO

''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009. In the 1920s,

Tennessee Valley Authority

''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009. TVA also gained control of TEPCO's assets after a legal struggle in the 1930s with TEPCO president Jo Conn Guild and attorney

In 1955, Oak Ridge High School became the first public school in Tennessee to be integrated. This occurred one year after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled

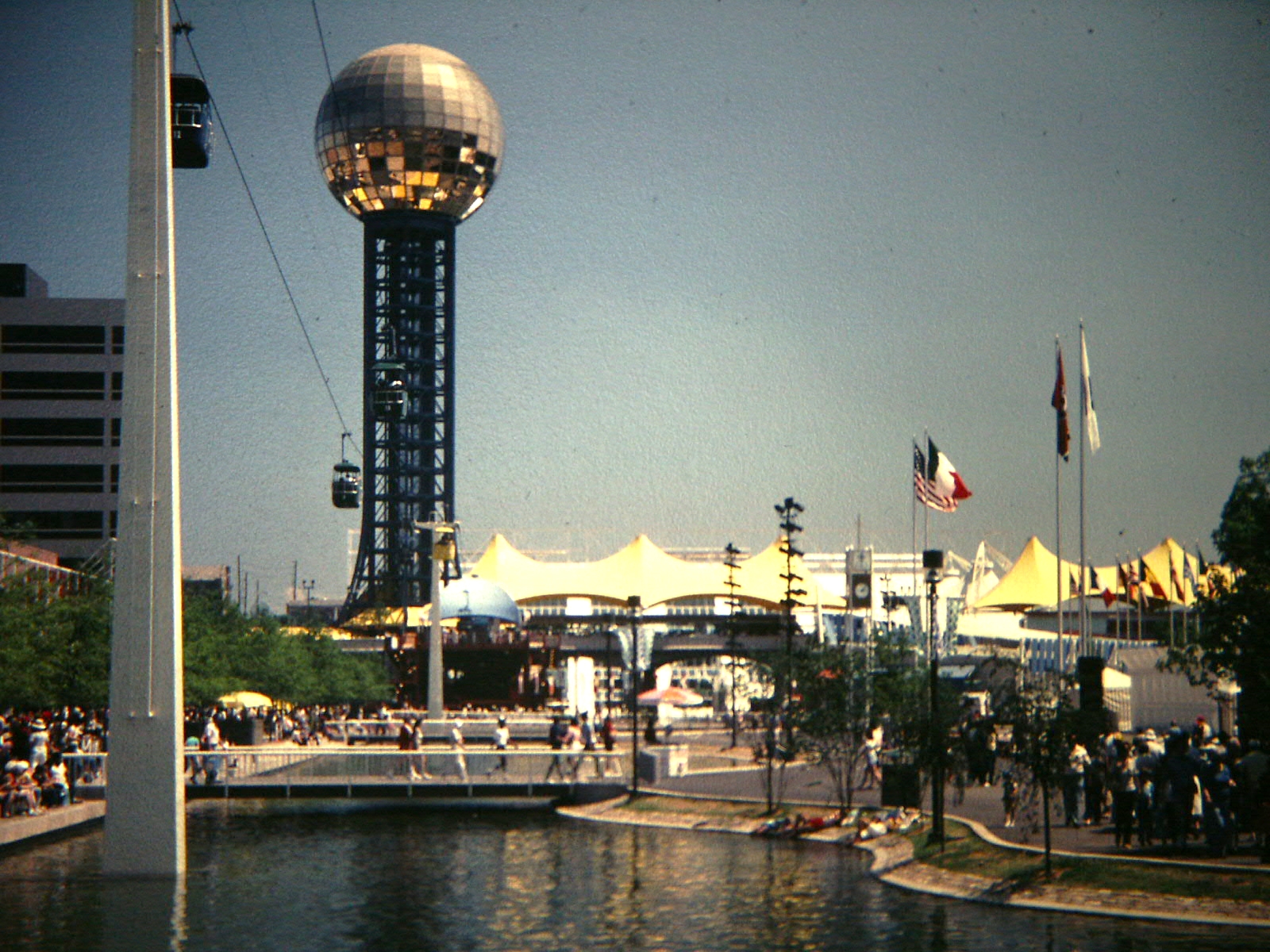

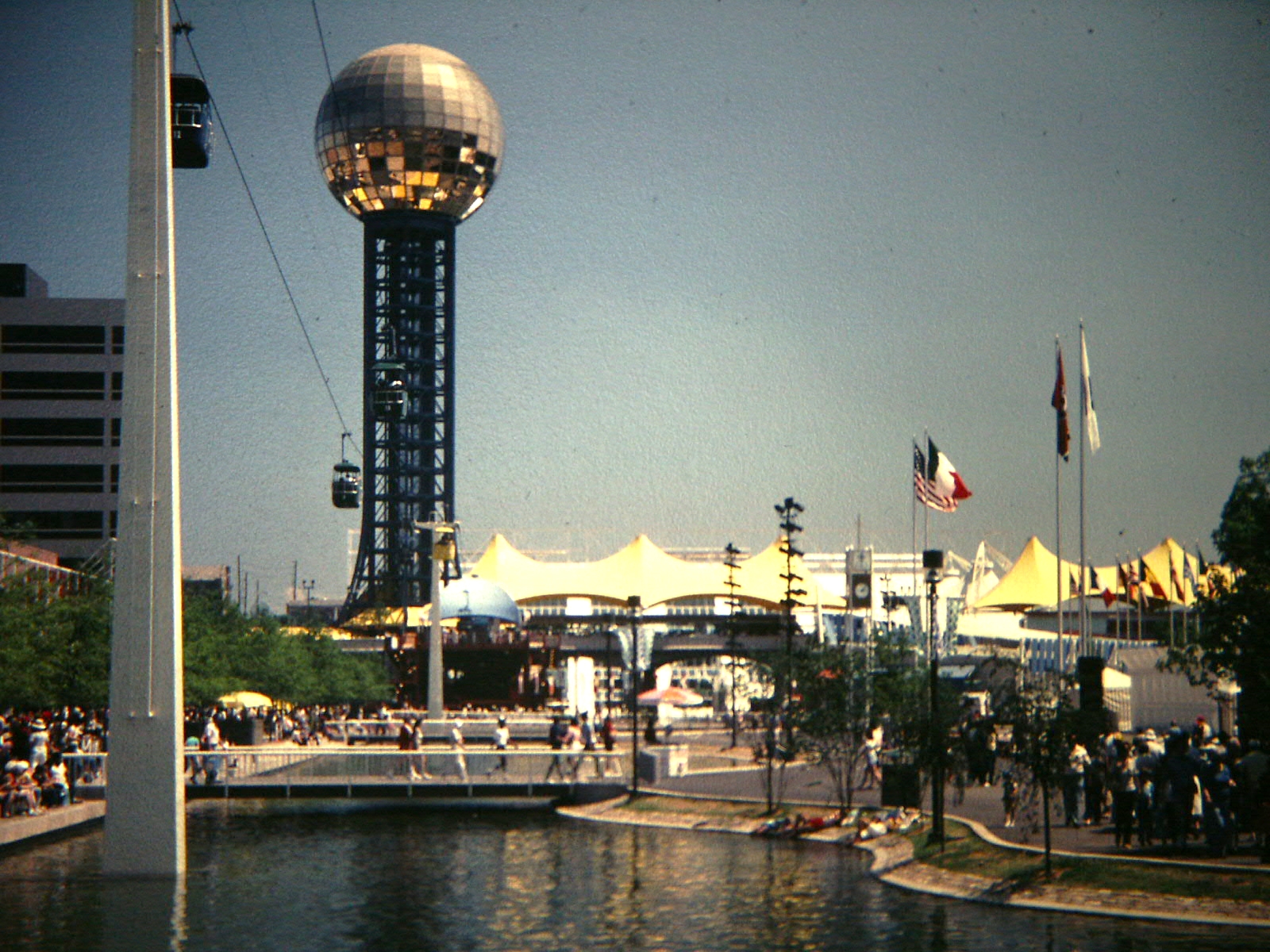

In 1955, Oak Ridge High School became the first public school in Tennessee to be integrated. This occurred one year after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled  In 1982, a

In 1982, a

The

The

While the mountain springs of East Tennessee and the cooler upper elevations of its mountainous areas have long provided a retreat from the region's summertime heat, much of East Tennessee's tourism industry is a result of land conservation movements in the 1920s and 1930s. The

While the mountain springs of East Tennessee and the cooler upper elevations of its mountainous areas have long provided a retreat from the region's summertime heat, much of East Tennessee's tourism industry is a result of land conservation movements in the 1920s and 1930s. The

College Football

''Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture'', 2002. Retrieved: August 18, 2009. The university's American football, football team plays at Neyland Stadium, one of the nation's largest stadiums. Neyland is flanked by the Thompson–Boling Arena, which has broken several attendance records for college men's and women's basketball.

Lawmakers to Redraw Districts Based Upon 2010 Population

''Chattanooga Times Free Press'', May 20, 2009. Retrieved: August 27, 2009. After the 2010 elections and the redistricting before 2012, though, the Republicans in control of state government made both the 3rd and 4th Districts significantly more Republican, and both are now on paper among the most Republican districts in the country.

East Tennessee Historical SocietyTravel and Discover East Tennessee

– Convention and Visitors Bureau section dedicated to East Tennessee. * {{Coord, 35.9, -84.1, display=title East Tennessee, Geography of Appalachia Regions of Tennessee State of Franklin

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

. East Tennessee consists of 33 counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

, 30 located within the Eastern Time Zone

The Eastern Time Zone (ET) is a time zone encompassing part or all of 23 states in the eastern part of the United States, parts of eastern Canada, the state of Quintana Roo in Mexico, Panama, Colombia, mainland Ecuador, Peru, and a small por ...

and three counties in the Central Time Zone

The North American Central Time Zone (CT) is a time zone in parts of Canada, the United States, Mexico, Central America, some Caribbean Islands, and part of the Eastern Pacific Ocean.

Central Standard Time (CST) is six hours behind Coordinate ...

, namely Bledsoe, Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, and Marion Marion may refer to:

People

*Marion (given name)

*Marion (surname)

*Marion Silva Fernandes, Brazilian footballer known simply as "Marion"

*Marion (singer), Filipino singer-songwriter and pianist Marion Aunor (born 1992)

Places Antarctica

* Mario ...

. East Tennessee is entirely located within the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

, although the landforms range from densely forested mountains to broad river valleys. The region contains the major cities of Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state' ...

and Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

, Tennessee's third and fourth largest cities, respectively, and the Tri-Cities, the state's sixth largest population center.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, many East Tennesseans remained loyal to the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

even as the state seceded and joined the Confederacy. Early in the war, Unionist delegates unsuccessfully attempted to split East Tennessee into a separate state that would remain as part of the Union. After the war, a number of industrial operations were established in cities in the region. The Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolina ...

(TVA), created by Congress during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

in the 1930s, spurred economic development and helped to modernize the region's economy and society. The TVA would become the nation's largest public utility

A public utility company (usually just utility) is an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service (often also providing a service using that infrastructure). Public utilities are subject to forms of public control and r ...

provider. Today, the TVA's administrative operations are headquartered in Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state' ...

and its power operations are based in Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

. Oak Ridge was the site of the world's first successful uranium enrichment

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 (written 235U) has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238 (238 ...

operations, which were used to construct the world's first atomic bombs, two of which were dropped on Imperial Japan at the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The Appalachian Regional Commission

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) is a United States federal–state partnership that works with the people of Appalachia to create opportunities for self-sustaining economic development and improved quality of life. Congress established A ...

further transformed the region in the late 20th century.

East Tennessee is both geographically and culturally part of Appalachia

Appalachia () is a cultural region in the Eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York State to northern Alabama and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Newfoundland and Labrador, Ca ...

, and has been included— along with Western North Carolina

Western North Carolina (often abbreviated as WNC) is the region of North Carolina which includes the Appalachian Mountains; it is often known geographically as the state's Mountain Region. It contains the highest mountains in the Eastern United ...

, North Georgia

North Georgia is the northern hilly/mountainous region in the U.S. state of Georgia. At the time of the arrival of settlers from Europe, it was inhabited largely by the Cherokee. The counties of north Georgia were often scenes of important eve ...

, Eastern Kentucky

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

* Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

* Eastern Air ...

, Southwest Virginia

Southwest Virginia, often abbreviated as SWVA, is a mountainous region of Virginia in the westernmost part of the commonwealth. Located within the broader region of western Virginia, Southwest Virginia has been defined alternatively as all Vir ...

, the state of West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

, western Maryland

upright=1.2, An enlargeable map of Maryland's 23 counties and one independent city

Western Maryland, also known as the Maryland Panhandle, is the portion of the U.S. state of Maryland that typically consists of Washington, Allegany, and Garret ...

, and southwestern Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

— in every major definition of the Appalachian region since the early 20th century. East Tennessee is home to the nation's most visited national park— the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is an American national park in the southeastern United States, with parts in North Carolina and Tennessee. The park straddles the ridgeline of the Great Smoky Mountains, part of the Blue Ridge Mountains, whi ...

— and hundreds of smaller recreational areas. East Tennessee is often considered the birthplace of country music

Country (also called country and western) is a genre of popular music that originated in the Southern and Southwestern United States in the early 1920s. It primarily derives from blues, church music such as Southern gospel and spirituals, ...

, due largely to the 1927 Victor recording sessions in Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

, and throughout the 20th and 21st centuries has produced a steady stream of musicians of national and international fame.Ted Olson and Ajay Kalra, "Appalachian Music: Examining Popular Assumptions". ''A Handbook to Appalachia: An Introduction to the Region'' (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2006), pp. 163–170.

Geography

Unlike the geographic designations of regions of most U.S. states, the term East Tennessee has legal as well as socioeconomic and cultural meaning. East Tennessee, along withMiddle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that composes roughly the central portion of the state. It is delineated according to state law as 41 of the state's 95 counties. Middle Tennessee contains the ...

and West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions (Tennessee), Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee River, Tennessee and Miss ...

, comprises one of the state's three Grand Divisions

The Grand Divisions are three geographic regions in the U.S. state of Tennessee, each constituting roughly one-third of the state's land area, that are geographically, culturally, legally, and economically distinct. The Grand Divisions are lega ...

, whose boundaries are defined by state law. East Tennessee has a total land area of , making it the second-largest among the state's Grand Divisions, behind Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that composes roughly the central portion of the state. It is delineated according to state law as 41 of the state's 95 counties. Middle Tennessee contains the ...

. East Tennessee's land area is approximately 32.90% of the state's total land area. The entirety of East Tennessee is both geographically and culturally part of Appalachia, and is usually also considered part of the Upland South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

. East Tennessee borders North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

to the east, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

to the northeast, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

to the north, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

to the south, and Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

in the extreme southwest corner.

According to custom, the boundary between East and Middle Tennessee roughly follows the dividing line between Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Central Time Zone

The North American Central Time Zone (CT) is a time zone in parts of Canada, the United States, Mexico, Central America, some Caribbean Islands, and part of the Eastern Pacific Ocean.

Central Standard Time (CST) is six hours behind Coordinate ...

. Exceptions to this rule are that Bledsoe, Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, and Marion Marion may refer to:

People

*Marion (given name)

*Marion (surname)

*Marion Silva Fernandes, Brazilian footballer known simply as "Marion"

*Marion (singer), Filipino singer-songwriter and pianist Marion Aunor (born 1992)

Places Antarctica

* Mario ...

Counties are legally defined as part of East Tennessee, despite being within Central Time. Sequatchie County, located between Marion and Bledsoe Counties, is legally part of Middle Tennessee, but is often considered part of East Tennessee. Sequatchie County has also been defined as part of East Tennessee in the past, and Marion County has been included in Middle Tennessee. Some of the northeastern counties of Middle Tennessee that supported the Union during the American Civil War, including Fentress and Pickett, are sometimes culturally considered part of East Tennessee.

Topography

East Tennessee is located within three major geological divisions of theAppalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

; the Blue Ridge Mountains

The Blue Ridge Mountains are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian Mountains range. The mountain range is located in the Eastern United States, and extends 550 miles southwest from southern Pennsylvania through Maryland, West Virgin ...

on the border with North Carolina in the east, the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians

The Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, also called the Ridge and Valley Province or the Valley and Ridge Appalachians, are a physiographic province of the larger Appalachian division and are also a belt within the Appalachian Mountains extending ...

(usually called the "Great Appalachian Valley

The Great Appalachian Valley, also called The Great Valley or Great Valley Region, is one of the major landform features of eastern North America. It is a gigantic trough—a chain of valley lowlands—and the central feature of the Appalachian M ...

" or "Tennessee Valley") in the center, and the Cumberland Plateau

The Cumberland Plateau is the southern part of the Appalachian Plateau in the Appalachian Mountains of the United States. It includes much of eastern Kentucky and Tennessee, and portions of northern Alabama and northwest Georgia. The terms "Alle ...

in the west, part of which is in Middle Tennessee. The southern tip of the Cumberland Mountains

The Cumberland Mountains are a mountain range in the southeastern section of the Appalachian Mountains. They are located in western Virginia, southwestern West Virginia, the eastern edges of Kentucky, and eastern middle Tennessee, including the ...

also extends into the region between the Cumberland Plateau and Ridge-and-Valley regions. Both the Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains are part of the larger Appalachian Plateau

The Appalachian Plateau is a series of rugged dissected plateaus located on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains. The Appalachian Mountains are a mountain range that run down the Eastern United States.

The Appalachian Plateau is the nor ...

.

The Blue Ridge section comprises the western section of the Blue Ridge Province, the crests of which forms most of the Tennessee-North Carolina border. At an average elevation of above sea level, this physiographic province contains the highest elevations in the state. The Blue Ridge region is subdivided into several subranges— the Iron Mountains,

The Blue Ridge section comprises the western section of the Blue Ridge Province, the crests of which forms most of the Tennessee-North Carolina border. At an average elevation of above sea level, this physiographic province contains the highest elevations in the state. The Blue Ridge region is subdivided into several subranges— the Iron Mountains, Unaka Range

The Unaka Range is a mountain range on the border of Tennessee and North Carolina, in the southeastern United States. It is a subrange of the Appalachian Mountains and is part of the Blue Ridge Mountains physiographic province. The Unakas stret ...

, and Bald Mountains

The Bald Mountains are a mountain range rising along the border between Tennessee and North Carolina in the southeastern United States. They are part of the Blue Ridge Mountain Province of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. The Bald Mountain ...

in the north, the Great Smoky Mountains

The Great Smoky Mountains (, ''Equa Dutsusdu Dodalv'') are a mountain range rising along the Tennessee–North Carolina border in the southeastern United States. They are a subrange of the Appalachian Mountains, and form part of the Blue Ridge ...

in the center, and the Unicoi Mountains

The Unicoi Mountains are a mountain range rising along the border between Tennessee and North Carolina in the southeastern United States. They are part of the Blue Ridge Mountain Province of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. The Unicois are ...

and the Little Frog and Big Frog Mountain areas in the south. Clingmans Dome, at , is the state's highest point, and is located in the Great Smoky Mountains along the Tennessee-North Carolina border. Most of the Blue Ridge section is heavily forested and protected by various state and federal entities, the largest of which include the Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is an American national park in the southeastern United States, with parts in North Carolina and Tennessee. The park straddles the ridgeline of the Great Smoky Mountains, part of the Blue Ridge Mountains, whi ...

and the Cherokee National Forest

The Cherokee National Forest is a United States National Forest located in the U.S. states of Tennessee and North Carolina that was created on June 14, 1920. The forest is maintained and managed by the United States Forest Service. It encompasse ...

. The Appalachian Trail

The Appalachian Trail (also called the A.T.), is a hiking trail in the Eastern United States, extending almost between Springer Mountain in Georgia and Mount Katahdin in Maine, and passing through 14 states.Gailey, Chris (2006)"Appalachian Tr ...

enters Tennessee in the Great Smoky Mountains, and roughly follows the border with North Carolina most of the distance to near the Roan Mountain, where it shifts entirely into Tennessee.

The Ridge-and-Valley division is East Tennessee's largest, lowest lying, and most populous section. It consists of a series of alternating and paralleling elongate ridges with broad river valleys in between, roughly oriented northeast-to-southwest. This section's most notable feature, the Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other names, ...

, forms at the confluence of the Holston and French Broad rivers in Knoxville, and flows southwestward to Chattanooga. The lowest point in East Tennessee, at an elevation of approximately , is found where the Tennessee River enters Alabama in Marion County. Other notable rivers in the upper Tennessee watershed include the Clinch

Clinch may refer to:

* Nail (fastener) or device to hold in this way

* Clinching, in metalworking

* Clinch fighting or the clinch, a grappling position in boxing or wrestling, a stand-up embrace

* Clinch County, Georgia, USA

* Clinch River, near T ...

, Nolichucky, Watauga Watauga can refer to:

;Places

*Watauga, Kentucky

* Watauga County, North Carolina

* Watauga, South Dakota

* Watauga, Tennessee

* Watauga, Texas

;Bodies of Water

* Watauga Lake in Tennessee

* The Watauga River in North Carolina and Tennessee

;Shi ...

, Emory Emory may refer to:

Places

* Emory, Texas, U.S.

* Emory (crater), on the moon

* Emory Peak, in Texas, U.S.

* Emory River, in Tennessee, U.S.

Education

* Emory and Henry College, or simply Emory, in Emory, Virginia, U.S.

* Emory University

...

, Little Tennessee, Hiwassee, Sequatchie, and Ocoee rivers. Notable "ridges" in the Ridge-and-Valley range, which exceed elevations much greater than most surrounding ridges and are commonly referred to as mountains, include Clinch Mountain

Clinch Mountain is a mountain ridge in the U.S. states of Tennessee and Virginia, lying in the ridge-and-valley section of the Appalachian Mountains. From its southern terminus at Kitts Point, which lies at the intersection of Knox, Union and Gr ...

, Bays Mountain

Bays Mountain is a ridge of the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, located in eastern Tennessee. It runs southwest to northeast, from just south of Knoxville to Kingsport.

Its southern segment is relatively low in elevation (up to about ). In som ...

, and Powell Mountain

Powell Mountain (or "Powells Mountain") is a mountain ridge of the Ridge-and-valley Appalachians of the Appalachian Mountains. It is a long and narrow ridge, running northeast to southwest, from about Norton, Virginia to near Tazewell, Tennessee ...

.

The Cumberland Plateau rises nearly above the Appalachian Valley, stretching from the Kentucky border in the north to the Georgia and Alabama borders in the south. It has an average elevation of , and consists mostly of flat-topped tablelands, although the northern section is slightly more rugged. The plateau also has many waterfalls and stream valleys separated by steep gorges. The "Tennessee Divide" runs along the western part of the plateau, and separates the watersheds of the Tennessee and Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

rivers. Plateau counties mostly east of this divide— i.e. Cumberland, Morgan, and Scott— are grouped with East Tennessee, whereas plateau counties west of this divide, such as Fentress, Van Buren, and Grundy, are considered part of Middle Tennessee. Most of the Sequatchie Valley

Sequatchie Valley is a relatively long and narrow valley in the U.S. state of Tennessee and, in some definitions, Alabama. It is generally considered to be part of the Cumberland Plateau region of the Appalachian Mountains; it was probably formed ...

, a long narrow valley in the southeastern part of the Cumberland Plateau, is in East Tennessee. The part of the Plateau east of the Sequatchie Valley is called Walden Ridge

Walden Ridge (or Walden's Ridge) is a mountain ridge and escarpment located in Tennessee, in the United States. It marks the eastern edge of the Cumberland Plateau and is generally considered part of it. Walden Ridge is about long, running g ...

. One notable detached section of the Plateau is Lookout Mountain

Lookout Mountain is a mountain ridge located at the northwest corner of the U.S. state of Georgia, the northeast corner of Alabama, and along the southeastern Tennessee state line in Chattanooga. Lookout Mountain was the scene of the 18th-cen ...

, which overlooks Chattanooga. West of Chattanooga, the Tennessee River flows through the plateau in the Tennessee River Gorge

The Tennessee River Gorge is a canyon formed by the Tennessee River known locally as Cash Canyon. It is the fourth largest river gorge in the Eastern United States. The gorge is cut into the Cumberland Plateau as the river winds its way into Alab ...

.

The Cumberland Mountains begin directly north of the Sequatchie Valley, and extend northward to the Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its rol ...

at the Tennessee-Kentucky-Virginia tripoint. While technically a separate physiographic region, the Cumberland Mountains are usually considered part of the Cumberland Plateau in Tennessee. The Cumberland Mountains reach elevations above in Tennessee, and their largest subrage is the Crab Orchard Mountains

The Crab Orchard Mountains are a rugged, detached range of the southern Cumberland Mountains. They are situated in East Tennessee atop the Cumberland Plateau just west of the plateau's eastern escarpment, and comprise parts of Morgan, Anderso ...

. The Cumberland Trail traverses the eastern escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains.

Counties

*Anderson

Anderson or Andersson may refer to:

Companies

* Anderson (Carriage), a company that manufactured automobiles from 1907 to 1910

* Anderson Electric, an early 20th-century electric car

* Anderson Greenwood, an industrial manufacturer

* Anderson ...

* Bledsoe

* Blount

*Bradley

Bradley is an English surname derived from a place name meaning "broad wood" or "broad meadow" in Old English.

Like many English surnames Bradley can also be used as a given name and as such has become popular.

It is also an Anglicisation of t ...

*Campbell Campbell may refer to:

People Surname

* Campbell (surname), includes a list of people with surname Campbell

Given name

* Campbell Brown (footballer), an Australian rules footballer

* Campbell Brown (journalist) (born 1968), American television ne ...

*Carter

Carter(s), or Carter's, Tha Carter, or The Carter(s), may refer to:

Geography United States

* Carter, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

* Carter, Mississippi, an unincorporated community

* Carter, Montana, a census-designated place

* Carter ...

* Claiborne

*Cocke Cocke is a surname (pronounced ''cock'', ''cox'' or ''coke'') and may refer to:

* Charles Lewis Cocke (1940- ) Professor of Physics at Kansas State University, winner of 2006 Davisson–Germer Prize in Atomic or Surface Physics

* Erle Cocke Jr. ...

*Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

*Grainger Grainger may refer to:

Places

*Grainger, Alberta, a locality in Canada

*Grainger County, Tennessee, a county located in Tennessee, United States

*Grainger Falls, a waterfall in Chalky Inland, Fiordland, New Zealand

*Grainger Market, a covered mark ...

*Greene

Greene may refer to:

Places United States

*Greene, Indiana, an unincorporated community

*Greene, Iowa, a city

*Greene, Maine, a town

** Greene (CDP), Maine, in the town of Greene

*Greene (town), New York

** Greene (village), New York, in the town ...

* Hamblen

*Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilt ...

*Hancock Hancock may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Hancock, Iowa

* Hancock, Maine

* Hancock, Maryland

* Hancock, Massachusetts

* Hancock, Michigan

* Hancock, Minnesota

* Hancock, Missouri

* Hancock, New Hampshire

** Hancock (CDP), New Hampshir ...

* Hawkins

*Jefferson Jefferson may refer to:

Names

* Jefferson (surname)

* Jefferson (given name)

People

* Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), third president of the United States

* Jefferson (footballer, born 1970), full name Jefferson Tomaz de Souza, Brazilian foo ...

*Johnson

Johnson is a surname of Anglo-Norman origin meaning "Son of John". It is the second most common in the United States and 154th most common in the world. As a common family name in Scotland, Johnson is occasionally a variation of ''Johnston'', a ...

* Knox

* Loudon

*Marion Marion may refer to:

People

*Marion (given name)

*Marion (surname)

*Marion Silva Fernandes, Brazilian footballer known simply as "Marion"

*Marion (singer), Filipino singer-songwriter and pianist Marion Aunor (born 1992)

Places Antarctica

* Mario ...

* McMinn

* Meigs

* Monroe

* Morgan

*Polk

Polk may refer to:

People

* James K. Polk, 11th president of the United States

* Polk (name), other people with the name

Places

*Polk (CTA), a train station in Chicago, Illinois

* Polk, Illinois, an unincorporated community

* Polk, Missouri ...

* Rhea

* Roane

* Scott

* Sevier

* Sullivan

* Unicoi

*Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

*Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

The Official Tourism Website of Tennessee has a definition of East Tennessee slightly different from the legal definition; the website excludes Cumberland County while including Grundy and Sequatchie Counties.

Climate

Most of East Tennessee has ahumid subtropical climate

A humid subtropical climate is a zone of climate characterized by hot and humid summers, and cool to mild winters. These climates normally lie on the southeast side of all continents (except Antarctica), generally between latitudes 25° and 40° ...

, with the exception of some of the higher elevations in the Blue Ridge and Cumberland Mountains, which are classified as a cooler mountain temperate or humid continental climate

A humid continental climate is a climatic region defined by Russo-German climatologist Wladimir Köppen in 1900, typified by four distinct seasons and large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and freezing ...

. As the highest-lying region in the state, East Tennessee averages slightly lower temperatures than the rest of the state, and has the highest rate of snowfall, which averages more than annually in the highest mountains, although many of the lower elevations often receive no snow. The lowest recorded temperature in state history, at , was recorded at Mountain City on December 30, 1917. Fog

Fog is a visible aerosol consisting of tiny water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air at or near the Earth's surface. Reprint from Fog can be considered a type of low-lying cloud usually resembling stratus, and is heavily influ ...

is extremely common in East Tennessee, especially in the Ridge-and-Valley region, and often presents a significant hazard to motorists.

Population and demographics

East Tennessee is the second most populous and most densely populated of the threeGrand Divisions

The Grand Divisions are three geographic regions in the U.S. state of Tennessee, each constituting roughly one-third of the state's land area, that are geographically, culturally, legally, and economically distinct. The Grand Divisions are lega ...

. At the 2020 census it had 2,470,105 inhabitants living in its 33 counties, and increase of 142,561, or 6.12%, over the 2010

File:2010 Events Collage New.png, From top left, clockwise: The 2010 Chile earthquake was one of the strongest recorded in history; The Eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in Iceland disrupts air travel in Europe; A scene from the opening ceremony of ...

figure of 2,327,544 residents. Its population was 35.74% of the state's total, and its population density was . Prior to the 2010 census, East Tennessee was the most populous of the state's Grand Divisions, but was surpassed by Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that composes roughly the central portion of the state. It is delineated according to state law as 41 of the state's 95 counties. Middle Tennessee contains the ...

, which contains the rapidly-growing Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and the ...

and Clarksville metropolitan areas.

Demographically, East Tennessee is one of the regions in the United States with one of the highest concentrations of people who identify as White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

or European American. In the 2010 census, every county in East Tennessee except for Knox and Hamilton, the two most populous counties, had a population that was greater than 90% White. In most counties in East Tennessee, persons of Hispanic or Latino

''Hispanic'' and '' Latino'' are ethnonyms used to refer collectively to the inhabitants of the United States who are of Spanish or Latin American ancestry (). While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, for example, by the United States ...

origins outnumber African Americans, which is uncommon in the Southeastern United States. Large African American populations are found in Chattanooga and Knoxville, as well as considerable populations in several smaller cities.

Cities and metropolitan areas

The major cities of East Tennessee areKnoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state' ...

, which is near the geographic center of the region; Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

, which is in southeastern Tennessee at the Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

border; and the " Tri-Cities" of Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

, Johnson City, and Kingsport, located in the extreme northeasternmost part of the state. Of the ten metropolitan statistical areas in Tennessee designated by the Office of Management and Budget

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is the largest office within the Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP). OMB's most prominent function is to produce the president's budget, but it also examines agency programs, pol ...

(OMB), six are in East Tennessee. Also designated by the OMB in East Tennessee are the Knoxville-Sevierville-La Follette, Chattanooga-Cleveland-Athens and Tri-Cities combined statistical area

Combined statistical area (CSA) is a United States Office of Management and Budget (OMB) term for a combination of adjacent metropolitan (MSA) and micropolitan statistical areas (µSA) across the 50 US states and the territory of Puerto Ric ...

s.

Knoxville, with about 190,000 residents, is the state's third largest city, and contains the state's third largest metropolitan area, with about 1 million residents. Chattanooga, with a population of more than 180,000, is the state's fourth largest city, and anchors a metropolitan area with more than 500,000 residents, of whom approximately one-third live in Georgia. The Tri-Cities, while defined by the Office of Management and Budget

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is the largest office within the Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP). OMB's most prominent function is to produce the president's budget, but it also examines agency programs, pol ...

as the Kingsport-Bristol and Johnson City metropolitan areas, are usually considered one population center, which is the third-most populous in East Tennessee and the fifth-largest statewide.

Most of East Tennessee's population is found in the Ridge-and Valley region, including that of its major cities. Other important cities in the Ridge and Valley region include Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

, Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, Maryville, Oak Ridge, Sevierville

Sevierville ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Sevier County, Tennessee, located in eastern Tennessee. The population was 17,889 at the 2020 United States Census.

History

Native Americans of the Woodland period were among the first human ...

, Morristown, and Greeneville. The region also includes the Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

and Morristown metropolitan areas, each of which contain more than 100,000 residents. The Blue Ridge section of the state is much more sparsely populated, its main cities being Elizabethton, Pigeon Forge

Pigeon Forge is a mountain resort city in Sevier County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a total population of 6,343. Situated just 5 miles (8 km) north of Great Smoky Mountains National Pa ...

, and Gatlinburg. Crossville is the largest city in the Plateau region, which is also sparsely populated.

Most residents of the East Tennessee region commute

Commute, commutation or commutative may refer to:

* Commuting, the process of travelling between a place of residence and a place of work

Mathematics

* Commutative property, a property of a mathematical operation whose result is insensitive to th ...

by car with the lack of alternative modes of transportation such as commuter rail

Commuter rail, or suburban rail, is a passenger rail transport service that primarily operates within a metropolitan area, connecting commuters to a central city from adjacent suburbs or commuter towns. Generally commuter rail systems are con ...

or regional bus systems. Residents of the metropolitan areas for Knoxville, Morristown, Chattanooga, and the Tri-Cities region have an estimated one-way commute of 23 minutes.

Congressional districts

East Tennessee includes all of the state's 1st, 2nd, and3rd

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* Second#Sexagesimal divisions of calendar time and day, 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (d ...

congressional districts, and part of the 4th district. The First District is concentrated around the Tri-Cities region and Upper East Tennessee. The Second District includes Knoxville

Knoxville is a city in and the county seat of Knox County in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 United States census, Knoxville's population was 190,740, making it the largest city in the East Tennessee Grand Division and the state' ...

and the mountain counties to the south. The Third District includes the Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

area and the counties north of Knoxville (the two areas are connected by a narrow corridor in eastern Roane County). The Fourth, which extends into an area southwest of Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and the ...

, includes several of East Tennessee's Cumberland Plateau

The Cumberland Plateau is the southern part of the Appalachian Plateau in the Appalachian Mountains of the United States. It includes much of eastern Kentucky and Tennessee, and portions of northern Alabama and northwest Georgia. The terms "Alle ...

counties.

History

Native Americans

Much of what is known about East Tennessee's prehistoric Native Americans comes as a result of the Tennessee Valley Authority's reservoir construction, as federal law required archaeological investigations to be conducted in areas that were to be flooded. Excavations at theIcehouse Bottom

Icehouse Bottom is a prehistoric Native American site in Monroe County, Tennessee, located on the Little Tennessee River in the southeastern United States. Native Americans were using the site as a semi-permanent hunting camp as early as 7500 BC, ...

site near Vonore revealed that Native Americans were living in East Tennessee on at least a semi-annual basis as early as 7,500 B.C. The region's significant Woodland period

In the classification of :category:Archaeological cultures of North America, archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 Common Era, BCE to European con ...

(1000 B.C. – 1000 A.D.) sites include Rose Island (also near Vonore) and Moccasin Bend

Moccasin Bend Archeological District is an archeological site in Chattanooga, Tennessee, that is part of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park unit. The National Park Service refers to it as one of the "most unique units found in ...

(near Chattanooga). During what archaeologists call the Mississippian period (c. 1000–1600 A.D.), East Tennessee's Indigenous inhabitants were living in complex agrarian societies

An agrarian society, or agricultural society, is any community whose economy is based on producing and maintaining crops and farmland. Another way to define an agrarian society is by seeing how much of a nation's total production is in agriculture ...

at places such as Toqua and Hiwassee Island

Hiwassee Island, also known as Jollys Island and Benham Island, is located in Meigs County, Tennessee, at the confluence of the Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers. It is about northeast of Chattanooga. The island was the second largest land mass on th ...

, and had formed a minor chiefdom known as Chiaha

Chiaha was a Native American chiefdom located in the lower French Broad River valley in modern East Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. They lived in raised structures within boundaries of several stable villages. These overlooked the ...

in the French Broad Valley. Spanish expeditions led by Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

, Tristan de Luna

Tristan (Latin/ Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to we ...

, and Juan Pardo all visited East Tennessee's Mississippian-period inhabitants during the 16th century. Some of the Native peoples who are known to have inhabited the region during this time include the Muscogee Creek

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsYuchi

The Yuchi people, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native American tribe based in Oklahoma.

In the 16th century, Yuchi people lived in the eastern Tennessee River valley in Tennessee. In the late 17th century, they moved south to Alabama, G ...

, and Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

.

By the early 18th century, most Natives in Tennessee had disappeared, very likely wiped out by diseases introduced by the Spaniards, leaving the region sparsely populated. The Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

began migrating into what is now East Tennessee from what is now Virginia in the latter 17th century, possibly to escape expanding European settlement and diseases in the north. The Cherokee established a series of towns concentrated in the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee valleys that became known as the " Overhill towns", as traders from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia had to cross "over" the mountains to reach them. Early in the 18th century, the Cherokee forced the remaining members of other Native American groups out of the state.

Pioneer period

The first recorded Europeans to reach what is now East Tennessee were three expeditions led by Spanish explorers:Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

in 1540–1541, Tristan de Luna

Tristan (Latin/ Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; cy, Trystan), also known as Tristram or Tristain and similar names, is the hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. In the legend, he is tasked with escorting the Irish princess Iseult to we ...

in 1559, and Juan Pardo in 1566–1567. Pardo recorded the name "Tanasqui" from a local Native American village, which evolved into the state's current name. In 1673, Abraham Wood

Abraham Wood (1610–1682), sometimes referred to as "General" or "Colonel" Wood, was an English fur trader, militia officer, politician and explorer of 17th century colonial Virginia. Wood helped build and maintained Fort Henry at the falls of ...

, a British fur trader, sent an expedition led by James Needham and Gabriel Arthur from Fort Henry in the Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colonial empire, English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertG ...

into Overhill Cherokee territory in modern-day northeastern Tennessee. Needham was killed during the expedition and Arthur was taken prisoner, and remained with the Cherokees for more than a year. Longhunter

A longhunter (or long hunter) was an 18th-century explorer and hunter who made expeditions into the American frontier for as much as six months at a time. Historian Emory Hamilton says that "The Long Hunter was peculiar to Southwest Virginia onl ...

s from Virginia explored much of East Tennessee in the 1750s and 1760s in expeditions which lasted several months or even years.

The Cherokee alliance with Britain during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

led to the construction of Fort Loudoun in 1756 near present-day Vonore, which was the first British settlement in what is now Tennessee. Fort Loudoun was the westernmost British outpost to that date, and was designed by John William Gerard de Brahm

John William Gerard de Brahm (1718 c. 1799) was a German cartographer, engineer and mystic.

Life

He was born in Koblenz, Germany, the eight child of a court musician employed by the Elector of Trier. He became "Captain Engineer" in the Imper ...

and constructed by forces under Captain Raymond Demeré. Shortly after its completion, Demeré relinquished command of the fort to his brother, Captain Paul Demeré. Hostilities erupted between the British and the Overhill Cherokees into an armed conflict, and a siege of the fort ended with its surrender in 1760. The next morning, Paul Demeré and a number of his men were killed in an ambush nearby, and most of the rest of the garrison was taken prisoner. A peace expedition led by Henry Timberlake

Henry Timberlake (1730 or 1735 – September 30, 1765) was a colonial Anglo-American officer, journalist, and cartographer. He was born in the Colony of Virginia and died in England. He is best known for his work as an emissary from the Briti ...

in 1761 provided later travelers with invaluable knowledge regarding the location of the Overhill towns and the customs of the Overhill Cherokee.

The end of the French and Indian War in 1763 brought a stream of explorers and traders into the region, among them additional longhunters. In an effort to mitigate conflicts with the Natives, Britain issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

, which forbade settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

. Despite this proclamation, migration across the mountains continued, and the first permanent European settlers began arriving in northeastern Tennessee in the late 1760s. In 1769, William Bean

William Bean (December 9, 1721-May 1782) was an American pioneer, longhunter, and Commissioner of the Watauga Association. He is accepted by historians as the first permanent European American settler of Tennessee.

Biography

William Bean was b ...

— an associate of famed explorer Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

— built what is generally acknowledged as Tennessee's first permanent Euro-American residence in Tennessee along the Watauga River in present-day Johnson City. Shortly thereafter, James Robertson and a group of migrants from North Carolina (some historians suggest they were refugees of the Regulator wars) formed the Watauga Settlement at Sycamore Shoals

The Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River, usually shortened to Sycamore Shoals, is a rocky stretch of river rapids along the Watauga River in Elizabethton, Tennessee. Archeological excavations have found Native Americans lived near the shoals s ...

in modern-day Elizabethton on lands leased from the Cherokees. In 1772, the Wataugans established the Watauga Association

The Watauga Association (sometimes referred to as the Republic of Watauga) was a semi-autonomous government created in 1772 by frontier settlers living along the Watauga River in what is now Elizabethton, Tennessee. Although it lasted only a few ...

, which was the first constitutional government west of the Appalachians, and the "germ cell" of the state of Tennessee. Most of these settlers were English or of primarily English descent, but nearly 20% of them were Scotch-Irish. In 1775, the settlers reorganized themselves into the Washington District

The Washington District is a Norfolk Southern Railway line in the U.S. state of Virginia that connects Alexandria, Virginia, Alexandria and Lynchburg, Virginia, Lynchburg. Most of the line was originally built from 1850 to 1860 by the Orange and ...

to support the cause of the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, which had begun months before. The following year, the settlers petitioned the Colony of Virginia to annex the Washington District to provide protection from Native American attacks, which was denied. Later that year, they petitioned the government of North Carolina to annex the Washington District, which was granted in November 1776.

In 1775, Richard Henderson negotiated a series of treaties with the Cherokee to sell the lands of the Watauga settlements at Sycamore Shoals

The Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River, usually shortened to Sycamore Shoals, is a rocky stretch of river rapids along the Watauga River in Elizabethton, Tennessee. Archeological excavations have found Native Americans lived near the shoals s ...

on the banks of the Watauga River

The Watauga River () is a large stream of western North Carolina and East Tennessee. It is long with its headwaters in Linville Gap to the South Fork Holston River at Boone Lake.

Course

The Watauga River rises from a spring near the base ...

in present-day Elizabethton. Later that year, Daniel Boone, under Henderson's employment, blazed a trail from Fort Chiswell

Chiswell , sometimes , is a small village at the southern end of Chesil Beach, in Underhill, on the Isle of Portland in Dorset. It is the oldest settlement on the island, having formerly been known as Chesilton. The small bay at Chiswell is ca ...

in Virginia through the Cumberland Gap

The Cumberland Gap is a pass through the long ridge of the Cumberland Mountains, within the Appalachian Mountains, near the junction of the U.S. states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. It is famous in American colonial history for its rol ...

, which became part of the Wilderness Road

The Wilderness Road was one of two principal routes used by colonial and early national era settlers to reach Kentucky from the East. Although this road goes through the Cumberland Gap into southern Kentucky and northern Tennessee, the other (mo ...

, a major thoroughfare for settlers into Tennessee and Kentucky. That same year, a faction of Cherokees led by Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe (ᏥᏳ ᎦᏅᏏᏂ, pronounced ''Tsiyu Gansini'', "he is dragging his canoe") (c. 1738 – February 29, 1792) was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee warriors who resisted colonists and United States settlers in the ...

— angry over the tribe's appeasement of European settlers— split off to form what became known as the Chickamauga faction, which was concentrated around what is now Chattanooga. The next year, the Chickamauga, aligned with British loyalists, attacked Fort Watauga at Sycamore Shoals. The warnings of Dragging Canoe's cousin Nancy Ward

''Nanyehi'' (Cherokee: ᎾᏅᏰᎯ: "One who goes about"), known in English as Nancy Ward (c. 1738 – 1822 or 1824), was a Beloved Woman and political leader of the Cherokee. She advocated for peaceful coexistence with European Americans and, ...

spared many settlers' lives from the initial attacks. In spite of Dragging Canoe's protests, the Cherokee were continuously induced to sign away most of the tribe's lands to the U.S. government.

During the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, the Wataugans supplied 240 militiamen (led by John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

) to the frontier force known as the Overmountain Men

The Overmountain Men were American frontiersmen from west of the Blue Ridge Mountains which are the leading edge of the Appalachian Mountains, who took part in the American Revolutionary War. While they were present at multiple engagements in t ...

, which defeated British loyalists at the Battle of Kings Mountain

The Battle of Kings Mountain was a military engagement between Patriot and Loyalist militias in South Carolina during the Southern Campaign of the American Revolutionary War, resulting in a decisive victory for the Patriots. The battle took pla ...

in 1780. Tennessee's first attempt at statehood was the State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin or the State of Frankland)Landrum, refers to the proposed state as "the proposed republic of Franklin; while Wheeler has it as ''Frankland''." In ''That's Not in My American History Boo ...

, formed in 1784 from three Washington District counties. Its capital was initially at Jonesborough and later Greeneville, and eventually grew to include eight counties. After several unsuccessful attempts at statehood, the State of Franklin rejoined North Carolina in 1788. North Carolina ceded the region to the federal government, which designated it as the Southwest Territory

The Territory South of the River Ohio, more commonly known as the Southwest Territory, was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1790, until June 1, 1796, when it was admitted to the United States a ...

on May 26, 1790. William Blount

William Blount (March 26, 1749March 21, 1800) was an American Founding Father, statesman, farmer and land speculator who signed the United States Constitution. He was a member of the North Carolina delegation at the Constitutional Convention o ...

was appointed as the territorial governor by President George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, and Blount and James White established the city of Knoxville as the territory's capital in 1791. The Southwest Territory recorded a population of 35,691 in the first United States census that year, about three-fourths of whom resided in what is now East Tennessee.

In addition to the English and Scotch-Irish settlers, there were also a number of Welsh families who settled in East Tennessee in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. These were large immigrant family groups who came from the Welsh towns of Llandeilo

Llandeilo () is a town and community in Carmarthenshire, Wales, situated at the crossing of the River Towy by the A483 on a 19th-century stone bridge. Its population was 1,795 at the 2011 Census. It is adjacent to the westernmost point of the ...

, Blaengweche, Llandyfan, Derwydd, Glanaman

Glanamman ( cy, Glanaman) is a Welsh mining village in the valley of the River Amman in Carmarthenshire. Glanamman has long been a stronghold of the Welsh language; village life is largely conducted in Welsh. Like the neighbouring village of Gar ...

, Garnant

Garnant is a Welsh mining village in the valley of the River Amman in Carmarthenshire, north of Swansea. Like the neighbouring village of Glanamman it experienced a coal-mining boom in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but the last big col ...

, Upper Brynamman, Lower Brynamman

Lower Brynamman is an electoral ward of Neath Port Talbot county borough in Brynamman, Wales.

Electoral ward

The electoral ward of Lower Brynamman forms part of the parish of Gwaun-Cae-Gurwen. The ward consists of some or all of the settle ...

, Rhosamman, Cwmllynfell

Cwmllynfell () is the name of a village, community and electoral ward in Neath Port Talbot county borough, Wales.

Amenities

Cwmllynfell has its own local rugby union team - Cwmllynfell RFC. Also, a bilingual primary school, supermarket, post o ...

, Tairgwaith, Gwain-Cae-Gurwen, Gwnfe, Twnllanan, Llanddeusant, Ystradfellte

Ystradfellte is a village and community in Powys, Wales, about north of Hirwaun, with 556 inhabitants. It belongs to the historic county of Brecknockshire (Breconshire) and the Fforest Fawr area of the Brecon Beacons National Park, beside the A ...

, Llandovery

Llandovery (; cy, Llanymddyfri ) is a market town and community in Carmarthenshire, Wales. It lies on the River Tywi and at the junction of the A40 and A483 roads, about north-east of Carmarthen, north of Swansea and west of Brecon.

Hi ...

, Laugharne

Laugharne ( cy, Talacharn) is a town on the south coast of Carmarthenshire, Wales, lying on the estuary of the River Tâf.

The ancient borough of Laugharne Township ( cy, Treflan Lacharn) with its Corporation and Charter is a unique survival ...

.

A larger group of settlers, entirely of English descent, arrived from Virginia's Middle Peninsula

The Middle Peninsula is the second of three large peninsulas on the western shore of Chesapeake Bay in Virginia, in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the Middle Peninsula was home to 92,886 people. It lies between the Northern Neck and ...

. These came from the Virginia counties of Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

, Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

, King and Queen, King William, Mathews, and Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, historic county in South East England, southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the Ceremonial counties of ...

, as well as two smaller groups from Buckingham

Buckingham ( ) is a market town in north Buckinghamshire, England, close to the borders of Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire, which had a population of 12,890 at the 2011 Census. The town lies approximately west of Central Milton Keynes, sou ...

and New Kent counties in Virginia. They arrived as a result of large landowners buying up land and expanding in such a way that smaller landholders had to leave the area to prosper. This massive wave essentially transplanted the population of English-descended small-holders from Virginia's Middle Peninsula

The Middle Peninsula is the second of three large peninsulas on the western shore of Chesapeake Bay in Virginia, in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the Middle Peninsula was home to 92,886 people. It lies between the Northern Neck and ...

to East Tennessee.

Antebellum period

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a series of land cessions were negotiated with the Cherokees as settlers pushed south of the Washington District. The 1791Treaty of Holston

The Treaty of Holston (or Treaty of the Holston) was a treaty between the United States government and the Cherokee signed on July 2, 1791, and proclaimed on February 7, 1792. It was negotiated and signed by William Blount, governor of the South ...

, negotiated by William Blount, established terms of relations between the United States and the Cherokees. The First Treaty of Tellico established the boundaries of the Treaty of Holston, and a series of treaties over the next two decades ceded small amounts of Cherokee lands to the U.S. government. In the Calhoun Treaty of 1819, the U.S. government purchased Cherokee lands between the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers. In anticipation of forced removal of the Cherokees, white settlers began moving into Cherokee lands in southeast Tennessee in the 1820s and 1830s.

East Tennessee was home to one of the nation's first abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

movements, which arose in the early 19th century. Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

s, who had migrated to the region from Pennsylvania in the 1790s, formed the Manumission Society of Tennessee in 1814. Notable supporters included Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

clergyman Samuel Doak

Samuel Doak (1749–1830) was an American Presbyterian clergyman, Calvinist educator, and a former slave owner in the early movement in the United States for the abolition of slavery.

Early life

Samuel Doak was born August 1, 1749, in Augusta Coun ...

, Tusculum College

Tusculum University is a private Presbyterian university with its main campus in Tusculum, Tennessee. It is Tennessee's first university and the 28th-oldest operating college in the United States.

In addition to its main campus, the institution ...

cofounder Hezekiah Balch

Hezekiah Balch, D.D. (1741–1810) was a Presbyterian minister and the founder of Greeneville College (Greeneville, Tennessee) in 1794. After the Civil War, Greeneville College merged with what is now Tusculum University.

Early life and edu ...

, and Maryville College

Maryville College is a private liberal arts college in Maryville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1819 by Presbyterian minister Isaac L. Anderson for the purpose of furthering education and enlightenment into the West. The college is one of the ...

president Isaac Anderson. In 1820, Elihu Embree established ''The Emancipator''— the nation's first exclusively abolitionist newspaper— in Jonesborough. After Embree's death, Benjamin Lundy

Benjamin Lundy (January 4, 1789August 22, 1839) was an American Quaker abolitionist from New Jersey of the United States who established several anti-slavery newspapers and traveled widely. He lectured and published seeking to limit slavery's expa ...

established the ''Genius of Universal Emancipation'' in Greeneville in 1821 to continue Embree's work. By the 1830s, however, the region's abolitionist movement had declined in the face of fierce opposition. The geography of East Tennessee, unlike parts of Middle and West Tennessee, did not allow for large plantation complexes, and as a result, slavery remained relatively uncommon in the region.

In the 1820s, the Cherokees established a government modeled on the U.S. Constitution, and located their capitol at New Echota

New Echota was the capital of the Cherokee Nation in the Southeast United States from 1825 until their forced removal in the late 1830s. New Echota is located in present-day Gordon County, in northwest Georgia, 3.68 miles north of Calhoun. I ...

in northern Georgia. In response to restrictive laws passed by the Georgia legislature, the Cherokees in 1832 moved their capital to the Red Clay Council Grounds in what is now Bradley County, a short distance north of the border with Georgia. A total of eleven general councils were held at the site between 1832 and 1838, during which the Cherokees rejected multiple compromises to surrender their lands east of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and move west. The 1835 Treaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia, by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party.

The treaty established ter ...

which was not approved by the National Council at Red Clay, stipulated that the Cherokee relocate to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

in present-day Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

, and provided a grace period until May 1838 for them to voluntarily migrate. In 1838 and 1839, U.S. troops forcibly removed nearly 17,000 Cherokees and about 2,000 Black people the Cherokees enslaved from their homes in southeastern Tennessee to Indian Territory. An estimated 4,000 died along the way. The operation was orchestrated from Fort Cass

Fort Cass was a fort located on the Hiwassee River in present-day Charleston, Tennessee, that served as the military operational headquarters for the entire Cherokee removal, an forced migration of the Cherokee known as the Trail of Tears from the ...

in Charleston, which was constructed on the site of the Indian agency

In United States history, an Indian agent was an individual authorized to interact with American Indian tribes on behalf of the government.

Background

The federal regulation of Indian affairs in the United States first included development of t ...

. In the Cherokee language

200px, Number of speakers

Cherokee or Tsalagi ( chr, ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ, ) is an endangered-to-moribund Iroquoian language and the native language of the Cherokee people. ''Ethnologue'' states that there were 1,520 Cherokee speaker ...